In a Lifetime

I wonder if there will be stories like this one about people in our own generation. Frankly, I doubt it.

I found a Wikipedia entry about a man named Henry Burrell. Listen to this: the man was a stand-up comedian who took an interest in platypuses. By loafing around platypus habitats in his free time, he learned how to build enclosures keep platypuses alive in captivity at a time when no one else could. He was honored by the British Government for this discovery with knighthood (or, at least, something close to it).

Listen to this: the man was a stand-up comedian who took an interest in platypuses. By loafing around platypus habitats in his free time, he learned how to build enclosures keep platypuses alive in captivity at a time when no one else could. He was honored by the British Government for this discovery with knighthood (or, at least, something close to it).

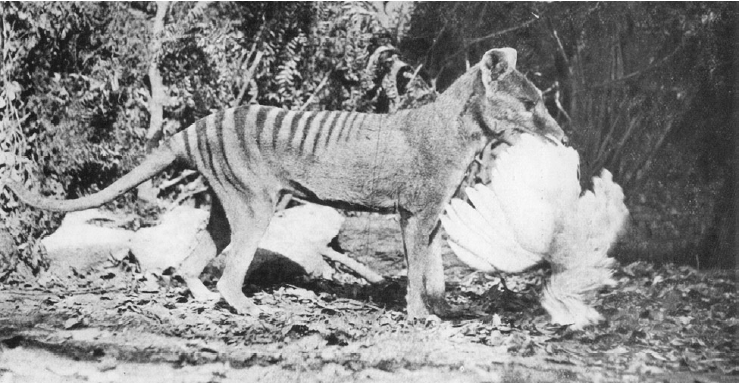

Sometime later, he took a photograph of a taxidermed thylacine (a foxlike creature from Tasmania) with a chicken in its mouth and submitted it to a newpaper. The photo, when printed, led farmers to believe the thylacine would prey on their poultry, even though the animal was no more of a danger to their hens than fingerless persons to string cheese. For fear of poultry-predation by roaming thylacines, farmers subsequently hunted the species to extinction!

Finally, before the man died he "was stricken with paralysis," but then, "recovered!"

All I can say is: What a life story!

That one person could have such storied adventures and misadventures in life is really quite flooring. Think of it: we're all brought up on candied expectations that we'll lead prolific lives. (I was convinced I'd be a professional baseball player and be president of the United States while curing cancer and designing my own videogames). But few people amass biographies that even begin to match the dynamism of early-life designs. I think the days when one person might realistically play many significant roles in a lifetime are simply gone.  Let's face it; the work of dilettantes today will not merit encyclopedic entry. The frontiers of knowledge in many fields, and especially in the biological sciences, have advanced far beyond the range of dabblers and tyros. To be a contributer to the scientific knowledgebase today you need not only a doctorate, but years of post-doctoral work and a gaggle of peer reviewed papers to your name as well.

Let's face it; the work of dilettantes today will not merit encyclopedic entry. The frontiers of knowledge in many fields, and especially in the biological sciences, have advanced far beyond the range of dabblers and tyros. To be a contributer to the scientific knowledgebase today you need not only a doctorate, but years of post-doctoral work and a gaggle of peer reviewed papers to your name as well.

So much for the desultory labors of stand-up comedians.

Perhaps the community is better off now that rigorously prepared scientists map out new waters. The thylacines certainly wouldn't complain.

As members of the community, we do benefit from better information than we used to, and innovation occurs at a higher pace than it did previously. But now that the contributions come from highly specialized cells of experts, what can the laity aspire to?

I'll tell you. We resign ourselves to wallow as consumers. We bath in the neon glow of television sets and internet news sites, waiting for scientists to conquer the unknown for us. Also, as if it were too demanding to refer to scientists by name, we assign the bunch a sobriquet, the third person plural pronoun: They.

Did you know that They discovered a new element today? What will They think of next?!

We leave exploration to someone with expertise - narrow, vertical focus achieved through the sacrifice of broad experience.

The era of the generalist is concluding. Fewer fascinating biographies like that of Henry Burrell, will exist. Our progression will be a tragedy for humanists, who appreciate the twists and turns of an adventurous lifetime. But as I mentioned earlier, the thylacines would not complain.